I think I’ve just got time for a quick post this lunchtime, so I’ll pick up on a topic that rose from a series of interchanges on Twitter this morning. As is the case with any interesting exchange of views, this conversation ended up quite some distance from its starting point, and I won’t have time to go all the way back to the beginning, but it was all to do with the “expansion of space“, a phrase one finds all over the place in books articles and web pages about cosmology at both popular and advanced levels.

What kicked the discussion off was an off-the-cuff humorous remark about the rate at which the Moon is receding from the Earth according to Hubble’s Law; the answer to which is “very slowly indeed”. Hubble’s law is  where

where  is the apparent recession velocity and

is the apparent recession velocity and  the distance, so for very small distance the speed of expansion is tiny. Strictly speaking, however, the velocity isn’t really observable – what we measure is the redshift, which we then interpret as being due to a velocity.

the distance, so for very small distance the speed of expansion is tiny. Strictly speaking, however, the velocity isn’t really observable – what we measure is the redshift, which we then interpret as being due to a velocity.

I chipped in with a comment to the effect that Hubble’s law didn’t apply to the Earth-Moon system (or to the whole Solar System, or for that matter to the Milky Way Galaxy or to the Local Group either) as these are held together by local gravitational effects and do not participate in the cosmic expansion.

To that came the rejoinder that surely these structures are expanding, just very slowly because they are small and that effect is counteracted by motions associated with local structures which “fight against” the “underlying expansion” of space.

But this also makes me uncomfortable, hence this post. It’s not that I think this is necessarily a misconception. The “expansion of space” can be a useful thing to discuss in a pedagogical context. However, as someone once said, teaching physics involves ever-decreasing circles of deception, and the more you think about the language of expanding space the less comfortable you should feel about it, and the more careful you should be in using it as anything other than a metaphor. I’d say it probably belongs to the category of things that Wolfgang Pauli would have described as “not even wrong”, in the sense that it’s more meaningless than incorrect.

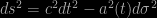

Let me briefly try to explain why. In cosmology we assume that the Universe is homogeneous and isotropic and consequently that the space-time is described by the Friedmann-Lemaître-Robertson-Walker metric, which can be written

in which  describes the (fixed) geometry of a three-dimensional homogeneous space; this spatial part does not depend on time. The imposition of spatial homogeneity selects a preferred time coordinate

describes the (fixed) geometry of a three-dimensional homogeneous space; this spatial part does not depend on time. The imposition of spatial homogeneity selects a preferred time coordinate  , defined such that observers can synchronize watches according to the local density of matter – points in space-time at which the matter density is the same are defined to be at the same time.

, defined such that observers can synchronize watches according to the local density of matter – points in space-time at which the matter density is the same are defined to be at the same time.

The presence of the scale factor  in front of the spatial 3-metric allows the overall 4-metric to change with time, but only in such a way that preserves the spatial geometry, in other words the spatial sections can have different scales at different times, but always have the same shape. It’s a consequence of Einstein’s equations of General Relativity that a Universe described by the FLRW metric must evolve with time (at least in the absence of a cosmological constant). In an expanding universe

in front of the spatial 3-metric allows the overall 4-metric to change with time, but only in such a way that preserves the spatial geometry, in other words the spatial sections can have different scales at different times, but always have the same shape. It’s a consequence of Einstein’s equations of General Relativity that a Universe described by the FLRW metric must evolve with time (at least in the absence of a cosmological constant). In an expanding universe  increases with

increases with  and this increase naturally accounts for Hubble’s law, with

and this increase naturally accounts for Hubble’s law, with  but only if you define velocities and distances in the particular way suggested by the coordinates used.

but only if you define velocities and distances in the particular way suggested by the coordinates used.

So how do we interpret this?

Well, there are (at least) two different interpretations depending on your choice of coordinates. One way to do it is to pick spatial coordinates such that the positions of galaxies change with time; in this choice the redshift of galaxy observed from another is due to their relative motion. Another way to do it is to use coordinates in which the galaxy positions are fixed; these are called comoving coordinates. In general relativity we can switch between one view and the other and the observable effect (i.e. the redshift) is the same in either.

Most cosmologists use comoving coordinates (because it’s generally a lot easier that way), and it’s this second interpretation that encourages one to think not about things moving but about space itself expanding. The danger with that is that it sometimes leads one to endow “space” (whatever that means) with physical attributes that it doesn’t really possess. This is most often seen in the analogy of galaxies being the raisins in a pudding, with “space” being the dough that expands as the pudding cooks taking the raisins away from each other. This analogy conveys some idea of the effect of homogeneous expansion, but isn’t really right. Raisins and dough are both made of, you know, stuff. Space isn’t.

In support of my criticism I quote:

Many semi-popular accounts of cosmology contain statements to the effect that “space itself is swelling up” in causing the galaxies to separate. This seems to imply that all objects are being stretched by some mysterious force: are we to infer that humans who survived for a Hubble time [the age of the universe] would find themselves to be roughly four metres tall? Certainly not….In the common elementary demonstration of the expansion by means of inflating a balloon, galaxies should be represented by glued-on coins, not ink drawings (which will spuriously expand with the universe).

(John Peacock, Cosmological Physics, p. 87-8). A lengthier discussion of this point, which echoes some of the points I make below, can be found here.

To get back to the original point of the question let me add another quote:

A real galaxy is held together by its own gravity and is not free to expand with the universe. Similarly, if [we talk about] the Solar System, Earth, [an] atom, or almost anything, the result would be misleading because most systems are held together by various forces in some sort of equilibrium and cannot partake in cosmic expansion. If we [talk about] clusters of galaxies…most clusters are bound together and cannot expand. Superclusters are vast sprawling systems of numerous clusters that are weakly bound and can expand almost freely with the universe.

(Edward Harrison, Cosmology, p. 278).

I’d put this a different way. The “Hubble expansion” describes the motion of test particles in a the coordinate system I described above, i.e one which applies to a perfectly homogeneous and isotropic universe. This metric simply doesn’t apply on the scale of the solar system, our own galaxy and even up to the scale of groups or clusters of galaxies. The Andromeda Galaxy (M31), for example, is not receding from the Milky Way at all – it has a blueshift. I’d argue that the space-time geometry in such systems is simply nothing like the FLRW form, so one can’t expect to make physical sense trying to to interpret particle motions within them in terms of the usual cosmological coordinate system. Losing the symmetry of the FLRW case makes the choice of appropriate coordinates much more challenging.

There is cosmic inhomogeneity on even larger scales, of course, but in such cases the “peculiar velocities” generated by the lumpiness can be treated as a (linear) correction to the pure Hubble flow associated with the background cosmology. In my view, however, in highly concentrated objects that decomposition into an “underlying expansion” and a “local effect” isn’t useful. I’d prefer simply to say that there is no Hubble flow in such objects. To take this to an extreme, what about a black hole? Do you think there’s a Hubble flow inside one of those, struggling to blow it up?

In fact the mathematical task of embedding inhomogeneous structures in an asymptotically FLRW background is not at all straightforward to do exactly, but it is worth mentioning that, by virtue of Birkhoff’s theorem, the interior of an exactly spherical cavity (i.e. void) must be described by the (flat) Minkowski metric. In this case the external cosmic expansion has absolutely no effect on the motion of particles in the interior.

I’ll end with this quote from the Fount of All Wisdom, Ned Wright,in response to the question Why doesn’t the Solar System expand if the whole Universe is expanding?

This question is best answered in the coordinate system where the galaxies change their positions. The galaxies are receding from us because they started out receding from us, and the force of gravity just causes an acceleration that causes them to slow down, or speed up in the case of an accelerating expansion. Planets are going around the Sun in fixed size orbits because they are bound to the Sun. Everything is just moving under the influence of Newton’s laws (with very slight modifications due to relativity). [Illustration] For the technically minded, Cooperstock et al. computes that the influence of the cosmological expansion on the Earth’s orbit around the Sun amounts to a growth by only one part in a septillion over the age of the Solar System.

The paper cited in this passage is well worth reading because it demonstrates the importance of the point I was trying to make above about using an appropriate coordinate system:

In the non–spherical case, it is generally recognized that the expansion of the universe does not have observable effects on local physics, but few discussions of this problem in the literature have gone beyond qualitative statements. A serious problem is that these studies were carried out in coordinate systems that are not easily comparable with the frames used for astronomical observations and thus obscure the physical meaning of the computations.

Now I’ve waffled on far too long so I’ll just finally recommend this paper entitled Expanding Space: The Root of All Evil and get back to work…