A strange paper by Gurzadyan and Penrose hit the Arxiv a week or so ago. It seems to have generated quite a lot of reaction in the blogosphere and has now made it onto the BBC News, so I think it merits a comment.

The authors claim to have found evidence that supports Roger Penrose‘s conformal cyclic cosmology in the form of a series of (concentric) rings of unexpectedly low variance in the pattern of fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background seen by the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP). There’s no doubt that a real discovery of such signals in the WMAP data would point towards something radically different from the standard Big Bang cosmology.

I haven’t tried to reproduce Gurzadyan & Penrose’s result in detail, as I haven’t had time to look at it, and I’m not going to rule it out without doing a careful analysis myself. However, what I will say here is that I think you should take the statistical part of their analysis with a huge pinch of salt.

Here’s why.

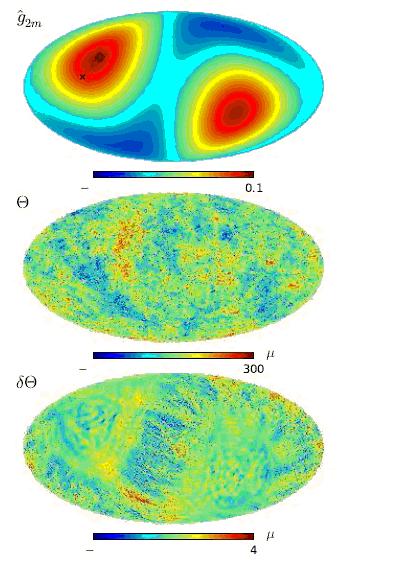

The authors report a hugely significant detection of their effect (they quote a “6-σ” result; in other words, the expected feature is expected to arise in the standard cosmological model with a probability of less than 10-7. The type of signal can be seen in their Figure 2, which I reproduce here:

Sorry they’re hard to read, but these show the variance measured on concentric rings (y-axis) of varying radius (x-axis) as seen in the WMAP W (94 Ghz) and V (54 Ghz) frequency channels (top two panels) compared with what is seen in a simulation with purely Gaussian fluctuations generated within the framework of the standard cosmological model (lower panel). The contrast looks superficially impressive, but there’s much less to it than meets the eye.

For a start, the separate WMAP W and V channels are not the same as the cosmic microwave background. There is a great deal of galactic foreground that has to be cleaned out of these maps before the pristine primordial radiation can be isolated. The fact similar patterns can be found in the BOOMERANG data by no means rules out a foreground contribution as a common explanation of anomalous variance. The authors have excluded the region at low galactic latitude (|b|<20°) in order to avoid the most heavily contaminated parts of the sky, but this is by no means guaranteed to eliminate foreground contributions entirely. Here is the all-sky WMAP W-band map for example:

Moreover, these maps also contain considerable systematic effects arising from the scanning strategy of the WMAP satellite. The most obvious of these is that the signal-to-noise varies across the sky, but there are others, such as the finite size of the beam of the WMAP telescope.

Neither galactic foregrounds nor correlated noise are present in the Gaussian simulation shown in the lower panel, and the authors do not say what kind of beam smoothing is used either. The comparison of WMAP single-channel data with simple Gaussian simulations is consequently deeply flawed and the significance level quoted for the result is certainly meaningless.

Having not looked looked at this in detail myself I’m not going to say that the authors’ conclusions are necessarily false, but I would be very surprised if an effect this large was real given the strenuous efforts so many people have made to probe the detailed statistics of the WMAP data; see, e.g., various items in my blog category on cosmic anomalies. Cosmologists have been wrong before, of course, but then so have even eminent physicists like Roger Penrose…

Another point that I’m not sure about at all is even if the rings of low variance are real – which I doubt – do they really provide evidence of a cyclic universe? It doesn’t seem obvious to me that the model Penrose advocates would actually produce a CMB sky that had such properties anyway.

Above all, I stress that this paper has not been subjected to proper peer review. If I were the referee I’d demand a much higher level of rigour in the analysis before I would allow it to be published in a scientific journal. Until the analysis is done satisfactorily, I suggest that serious students of cosmology shouldn’t get too excited by this result.

It occurs to me that other cosmologists out there might have looked at this result in more detail than I have had time to. If so, please feel free to add your comments in the box…

IMPORTANT UPDATE: 7th December. Two papers have now appeared on the arXiv (here and here) which refute the Gurzadyan-Penrose claim. Apparently, the data behave as Gurzadyan and Penrose claim, but so do proper simulations. In otherwords, it’s the bottom panel of the figure that’s wrong.

ANOTHER UPDATE: 8th December. Gurzadyan and Penrose have responded with a two-page paper which makes so little sense I had better not comment at all.