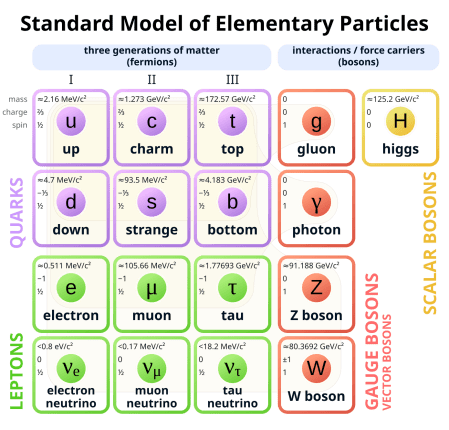

The big news in Irish physics this week was the announcement that Ireland’s application to join the European Organisation for Nuclear Research (CERN) has been accepted in principle, and the country is expected to become an associate member in 2026. The formal process to join began in late 2023, as described here. Maynooth University responded to the news in positive fashion here, including the statement that

This important decision represents a transformative step for Irish science, research, and innovation, unlocking unparalleled opportunities for students, researchers, and industry.

I think this is a very good move for Irish physics, and indeed for Ireland generally. I will, however, repeat a worry that I have expressed previously. There is an important point about CERN membership, however, which I hope is not sidelined. The case for joining CERN made at political levels is largely about the return in terms of the potential in contracts to technology companies based in Ireland from instrumentation and other infrastructure investments. This was also the case for Ireland’s membership of the European Southern Observatory, which Ireland joined almost 7 years ago. The same thing is true for involvement in the European Space Agency, which Ireland joined in 1975. These benefits are of course real and valuable and it is entirely right that arguments should involve them.

Looking at CERN membership from a purely scientific point of view, however, the return to Ireland will be negligible unless there is a funding to support scientific exploitation of the facility. That would include funding for academic staff time, and for postgraduate and postdoctoral researchers to build up an active community as well as, e.g., computing facilities. This need not be expensive even relative to the modest cost of associate membership (approximately €1.9M). I would estimate a figure of around half that would be needed to support CERN-based science.

The problem is that research funding for fundamental science (such as particle physics) in Ireland has been so limited as to be virtually non-existent by a matter of policy at Science Foundation Ireland, which basically only funded applied research. Even if it were decided to target funding for CERN exploitation, unless there is extra funding that would just lead to the jam being spread even more thinly elsewhere.

As I have mentioned before, Ireland’s membership of ESO provides a cautionary tale. The Irish astronomical community was very happy about the decision to join ESO, but that decision was not accompanied by significant funding to exploit the telescopes. Few astronomers have therefore been able to benefit from ESO membership. While there are other benefits of course, the return to science has been extremely limited. The phrase “to spoil a ship for a ha’porth of tar” springs to mind.

Although Ireland joined ESA almost fifty years ago, the same issue applies there. ESA member countries pay into a mandatory science programme which includes, for example, Euclid. However, did not put any resources on the table to allow full participation in the Euclid Consortium. There is Irish involvement in other ESA projects (such as JWST) but this is somewhat piecemeal. There is no funding programme in Ireland dedicated to the scientific exploitation of ESA projects.

Under current arrangements the best bet in Ireland for funding for ESA, ESO or CERN exploitation is via the European Research Council, but to get a grant from that one has to compete with much better developed communities in those areas.

The recent merger of Science Foundation Ireland and the Irish Research Council to form a single entity called Research Ireland perhaps provides an opportunity to correct this shortfall. If I had any say in the new structure I would set up a pot of money specifically for the purposes I’ve described above. Funding applications would have to be competitive, of course, and I would argue for a panel with significant international representation to make the decisions. But for this to work the overall level of public sector research funding will have to increase dramatically from its current level, well below the OECD average. Ireland is currently running a huge Government surplus which is projected to continue growing until at least 2026. Only a small fraction of that surplus would be needed to build viable research communities not only in fundamental science but also across a much wider range of disciplines. Failure to invest now would be a wasted opportunity. There is currently no evidence of the required uplift in research spending despite the better-than-healthy state of Government finances.