There’s been a lot of news coverage this week about a very big black hole, so I thought I’d post a little bit of background. The paper describing the discovery of the object concerned appeared in Nature this week, but basically it’s a quasar at a redshift z=6.30. That’s not the record for such an object. Not long ago I posted an item about the discovery of a quasar at redshift 7.085, for example. But what’s interesting about this beastie is that it’s a very big beastie, with a central black hole estimated to have a mass of around 12 billion times the mass of the Sun, which is a factor of ten or more larger than other objects found at high redshift.

Anyway, I thought perhaps it might be useful to explain a little bit about what difficulties this observation might pose for the standard “Big Bang” cosmological model. Our general understanding of galaxies form is that gravity gathers cold non-baryonic matter into clumps into which “ordinary” baryonic material subsequently falls, eventually forming a luminous galaxy forms surrounded by a “halo” of (invisible) dark matter. Quasars are galaxies in which enough baryonic matter has collected in the centre of the halo to build a supermassive black hole, which powers a short-lived phase of extremely high luminosity.

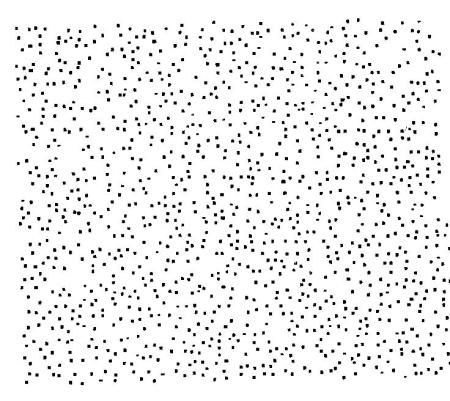

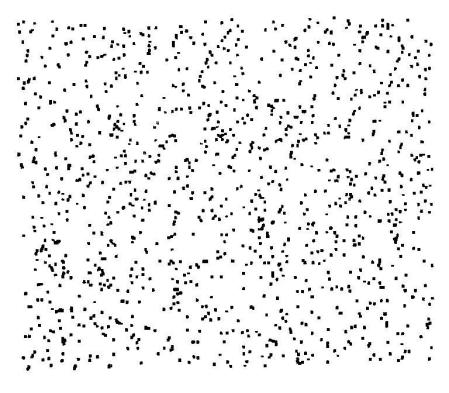

The key idea behind this picture is that the haloes form by hierarchical clustering: the first to form are small but merge rapidly into objects of increasing mass as time goes on. We have a fairly well-established theory of what happens with these haloes – called the Press-Schechter formalism – which allows us to calculate the number-density of objects of a given mass

as a function of redshift

. As an aside, it’s interesting to remark that the paper largely responsible for establishing the efficacy of this theory was written by George Efstathiou and Martin Rees in 1988, on the topic of high redshift quasars.

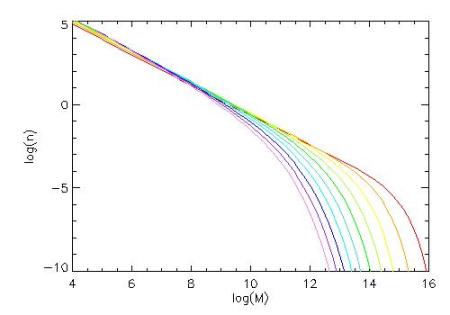

Anyway, this is how the mass function of haloes is predicted to evolve in the standard cosmological model; the different lines show the distribution as a function of redshift for redshifts from 0 (red) to 9 (violet):

Note that the typical size of a halo increases with decreasing redshift, but it’s only at really high masses where you see a really dramatic effect. The plot is logarithmic, so the number density large mass haloes falls off by several orders of magnitude over the range of redshifts shown. The mass of the black hole responsible for the recently-detected high-redshift quasar is estimated to be about . But how does that relate to the mass of the halo within which it resides? Clearly the dark matter halo has to be more massive than the baryonic material it collects, and therefore more massive than the central black hole, but by how much?

This question is very difficult to answer, as it depends on how luminous the quasar is, how long it lives, what fraction of the baryons in the halo fall into the centre, what efficiency is involved in generating the quasar luminosity, etc. Efstathiou and Rees argued that to power a quasar with luminosity of order for a time order

years requires a parent halo of mass about

. Generally, i’s a reasonable back-of-an-envelope estimate that the halo mass would be about a hundred times larger than that of the central black hole so the halo housing this one could be around

.

You can see from the abundance of such haloes is down by quite a factor at redshift 7 compared to redshift 0 (the present epoch), but the fall-off is even more precipitous for haloes of larger mass than this. We really need to know how abundant such objects are before drawing definitive conclusions, and one object isn’t enough to put a reliable estimate on the general abundance, but with the discovery of this object it’s certainly getting interesting. Haloes the size of a galaxy cluster, i.e. , are rarer by many orders of magnitude at redshift 7 than at redshift 0 so if anyone ever finds one at this redshift that would really be a shock to many a cosmologist’s system, as would be the discovery of quasars with such a high mass at redshifts significantly higher than seven.

Another thing worth mentioning is that, although there might be a sufficient number of potential haloes to serve as hosts for a quasar, there remains the difficult issue of understanding precisely how the black hole forms and especially how long it takes to do so. This aspect of the process of quasar formation is much more complicated than the halo distribution, so it’s probably on detailed models of black-hole growth that this discovery will have the greatest impact in the short term.

Follow @telescoper